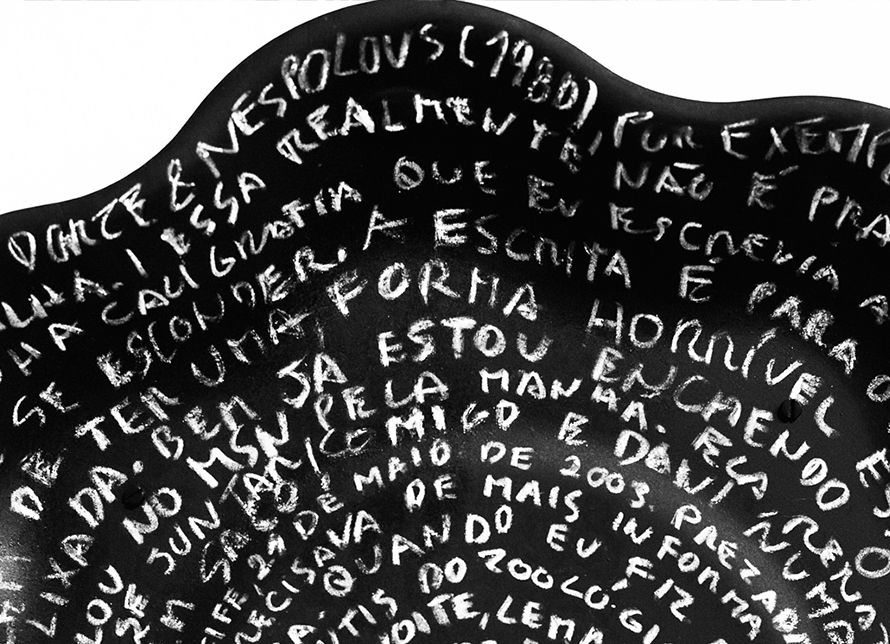

Canibalizar-se

Text Clarissa Diniz

Offering her intimacies on trays of grief, Juliana impels us to serve ourselves more of her, and, so, in an anthropophagical way, we gradually take on her troubles. This is how her series Diário de Bandeja (Diary of a Tray) is presented — although easily adaptable to autobiographical classifications related to contemporary art production — as just another subtly perverse act of her work. Accustomed to situations of tension from an early age and, in a certain sense, to penitence, once again Juliana delivers us her sufferings. This time round, owning up to them. Eu não vou carregar esta cruz (I´m not going to carry this cross) determines the cathartic role of her recent production. Degenerative in tone, her works shift her idiosyncrasies: they transform memories into relics, present into past, part into whole, experience into watchfulness.

Notari assaults her childhood, her daily reality, her imagination and, in her unveiling action — turned metaphor in the work Ferida da Bienal (Wound(ed) from the Bienniale) —, makes visible the sores hidden beneath the gelid white that covers part of her works in a possible attempt to smarten her anguish and make her worries more seductive and attractive to the foreign eye. Such a libidinous inclination bears witness to the pulsations of life that, it seems to me, drive the artist in her anthropological moves. Despite the destruction of her alcove (and here alcove is a metaphor for subject), it is vital energy — the erect penis — that stands out amidst the pain. Overcoming martyrdom, there is in Juliana Notari a certain glorification of degenerative processes — probably like a bet upon continuity and transformation. Even though, for example, she presents her fat nature as a reason for watchfulness and, hence, restlessness, the artist insists in cultivating greed in her videoperformance and thus, transforms her suffering (death) into pleasure (life) for those who devour her: cannibalism. In a certain sense, the idea hovers over her catharsis, that symbolically supping together1, we will be, upon sharing her, dispersing her death. She does not want to carry her cross alone. And thus Notari joins a small group of artists — like Louise Bourgeois — whose work refers less to art than to human nature. The strength of her works comes from her existential appeal, and, in this sense, the autobiographical character of her production is less an aesthetic than a condition of its origins. As with Bourgeois, her diary is not an artistic option, but an egocentric demand that now Juliana risks transposing to the field of art. As with all translation, the transposition carried out by the artist establishes linguistic noises and misunderstandings that are not delivered on a tray (de bandeja). The innate mystery to her works — almost always minimally narrative — corrodes the possibility of establishing a single outline for her conflicts. As in Esqueci meu tamanco no quintal (I forgot my clog in the garden), each leg walks in one direction, and the sense of the route now ahead is also given by us who with her, from there on, share intimate secrets.

*Every anthropophagical/cannibal act, even when real, is symbolic. Hence there is no need for the presence of the artist, who, thus, emphasizes the psychoanalytical character of her work.